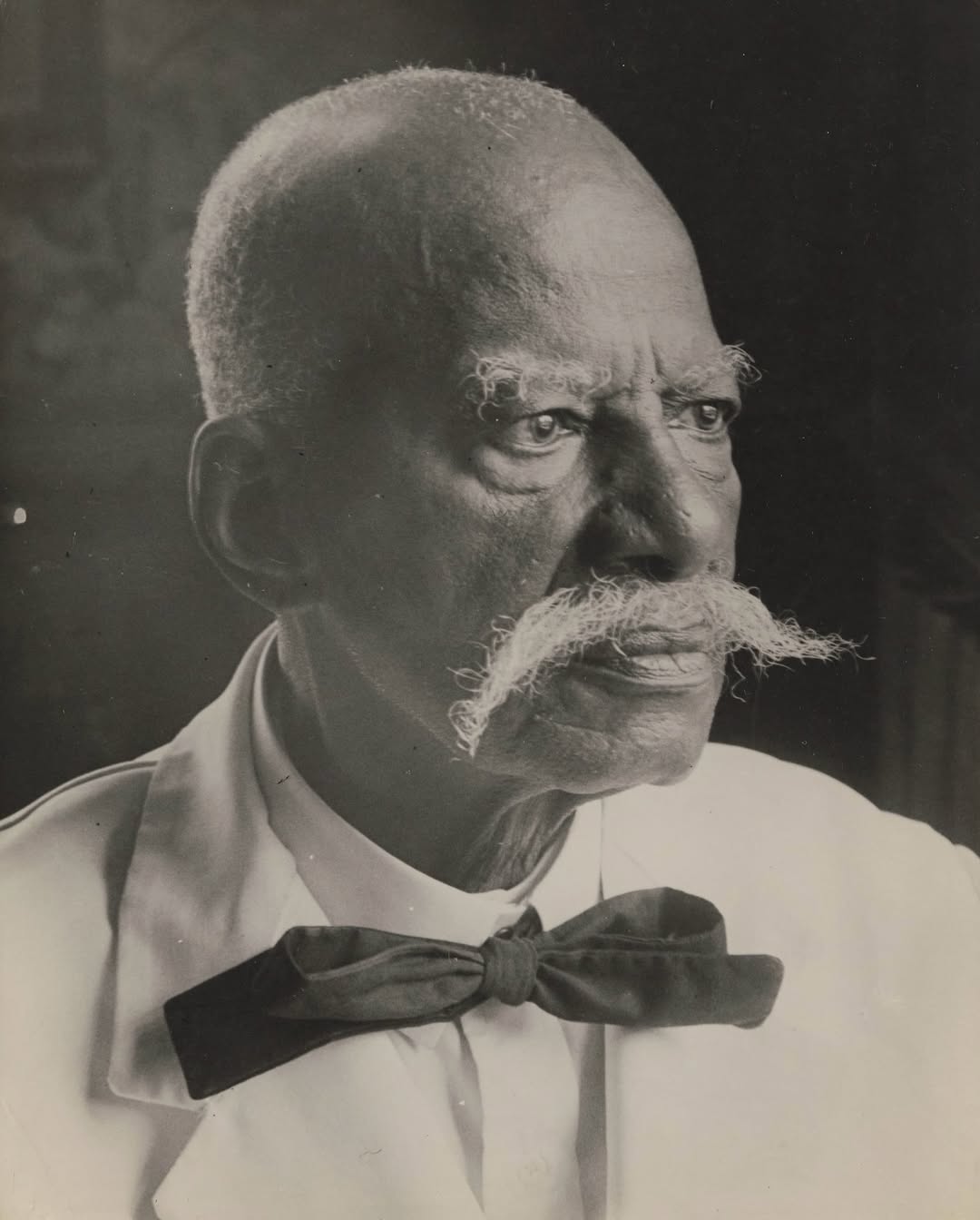

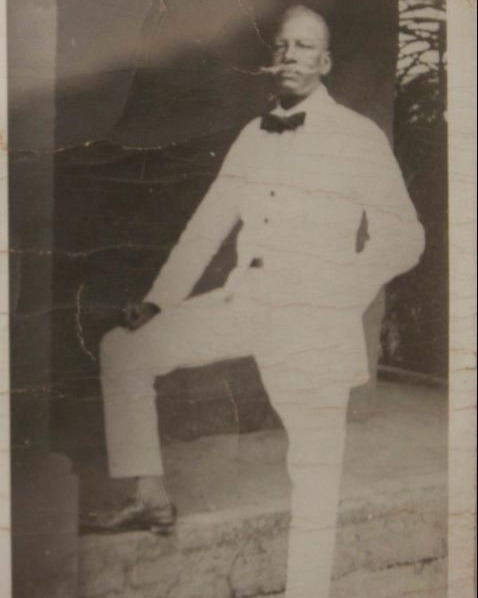

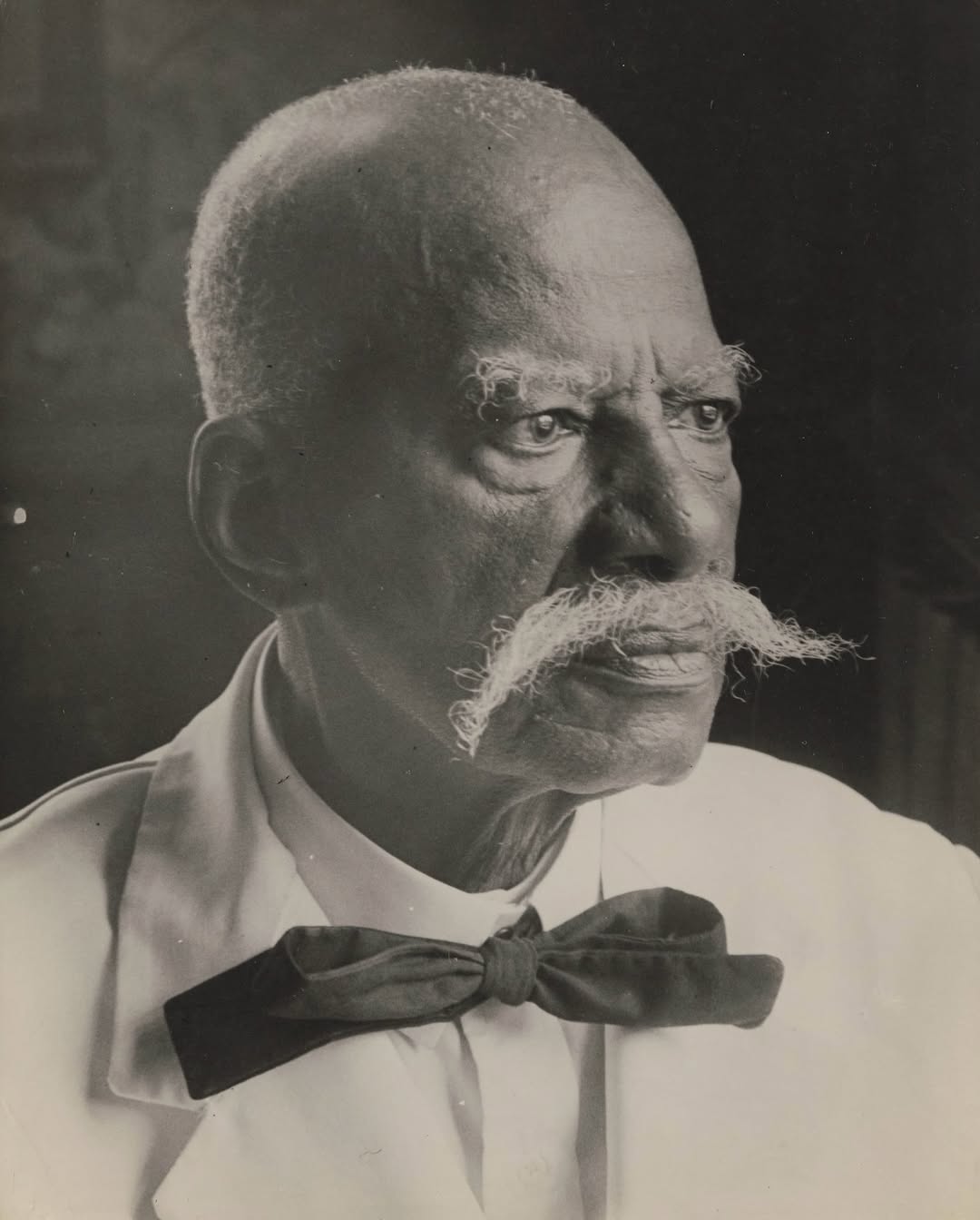

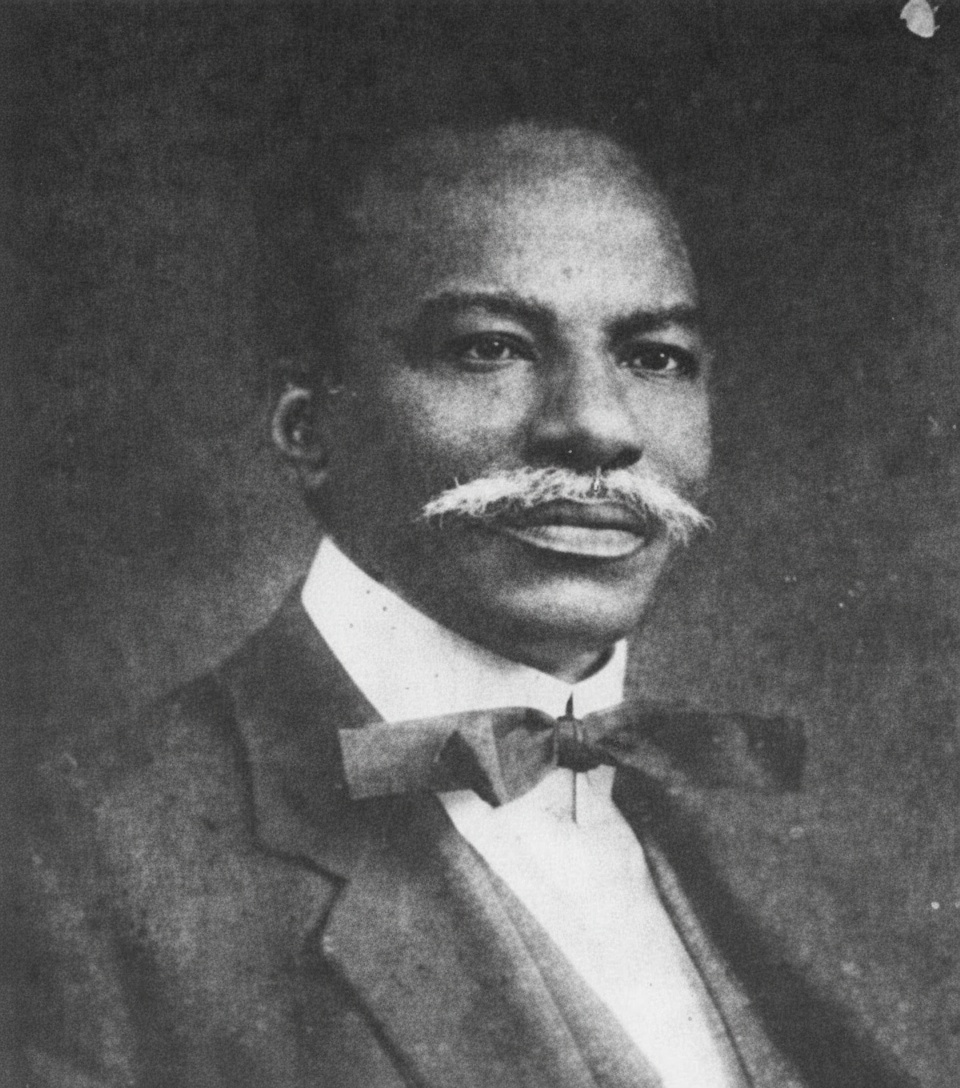

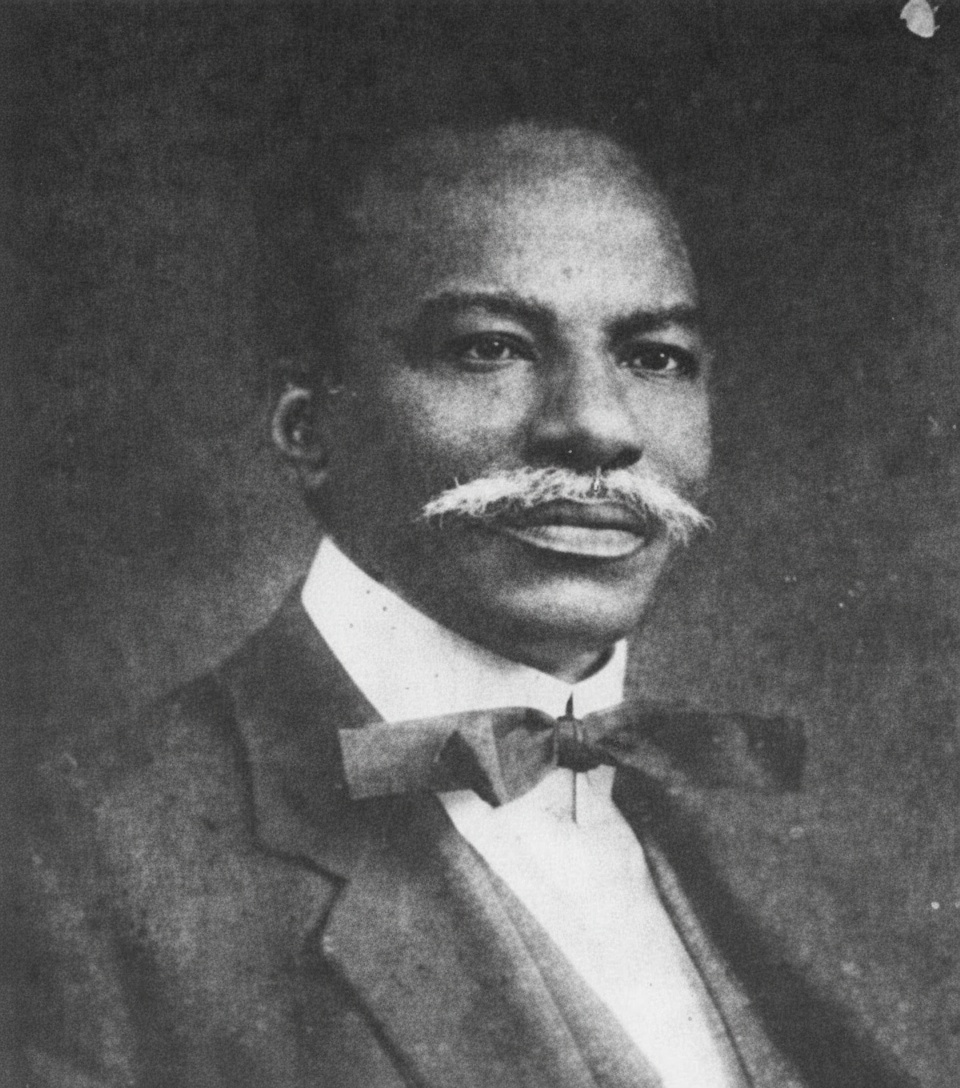

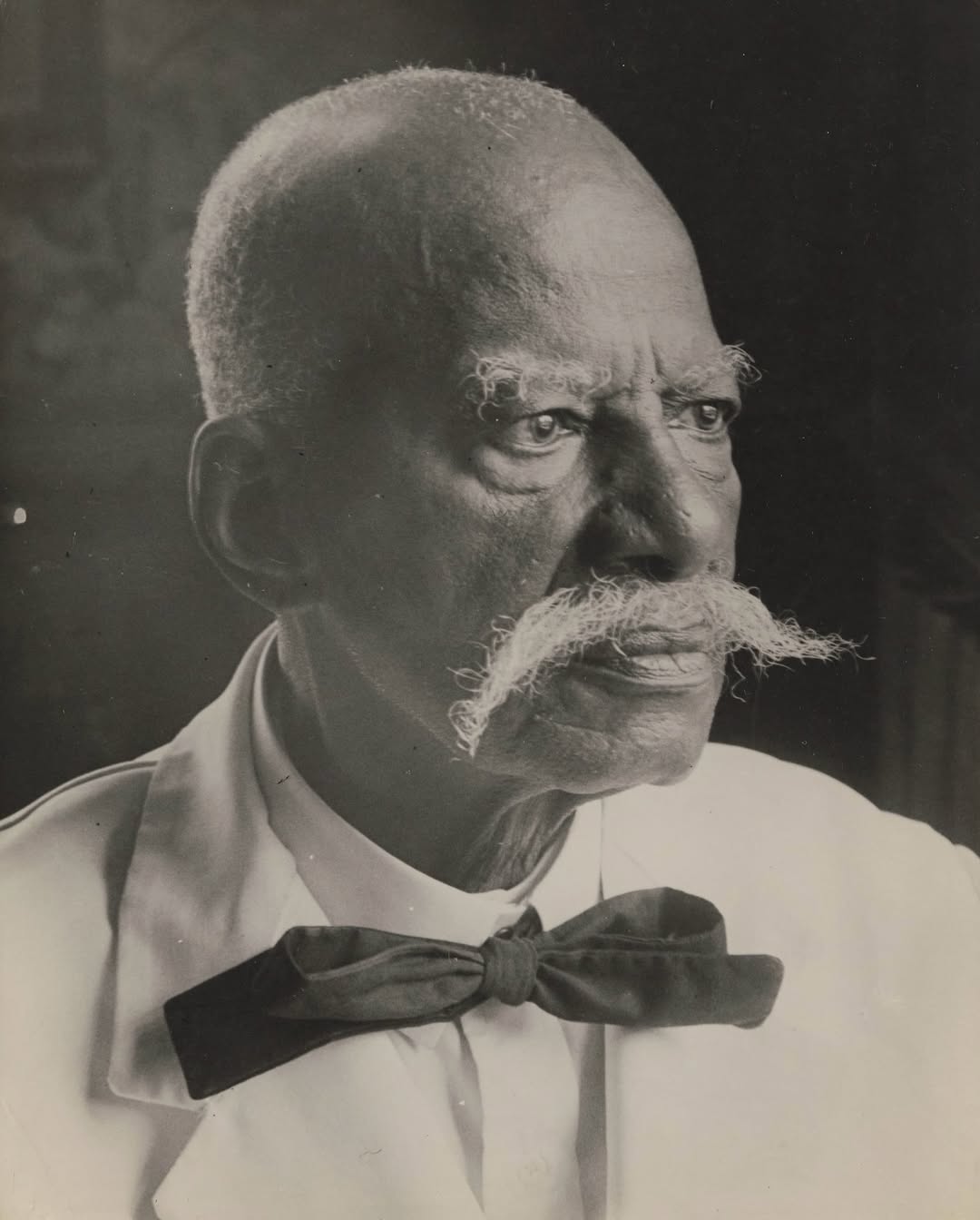

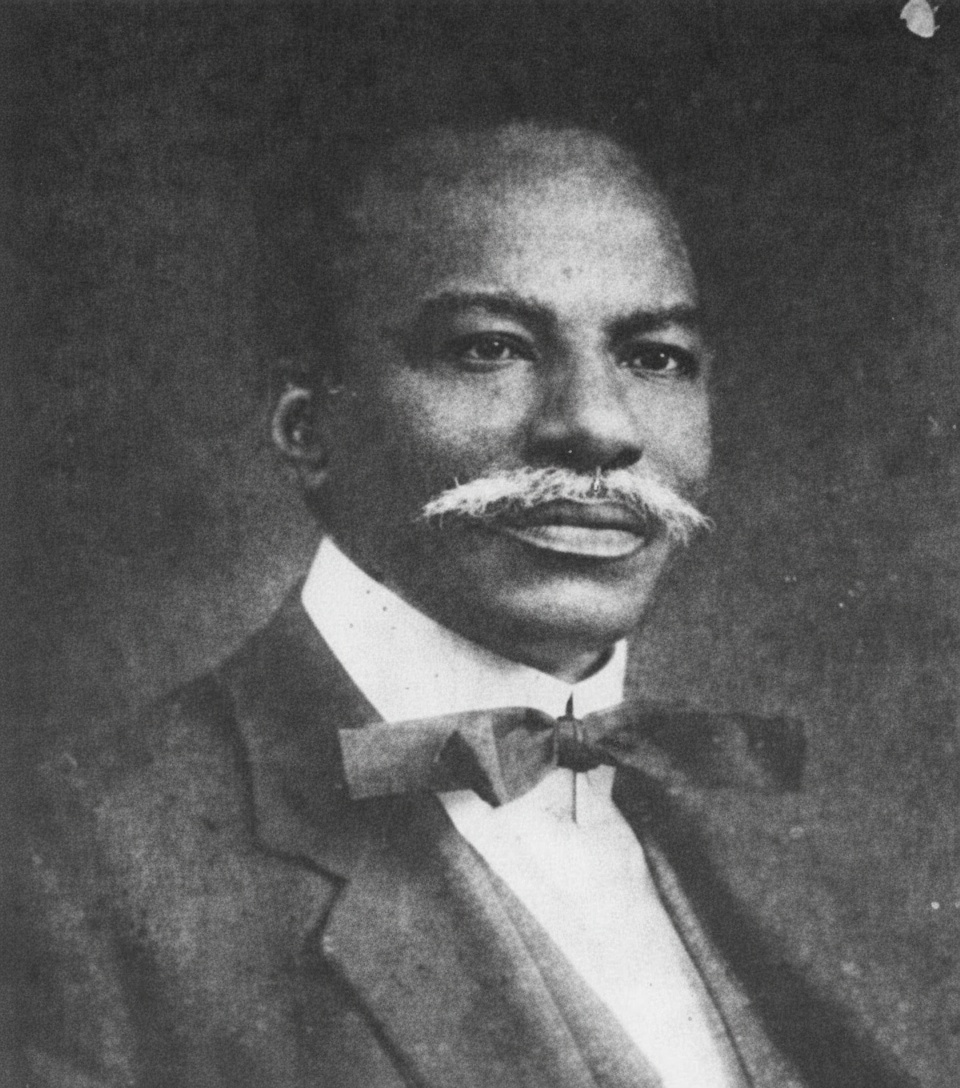

Herbert Macaulay

tells his own story.

Prologue:

The Seed of a Nation

Royal Beginnings (1864-1877)

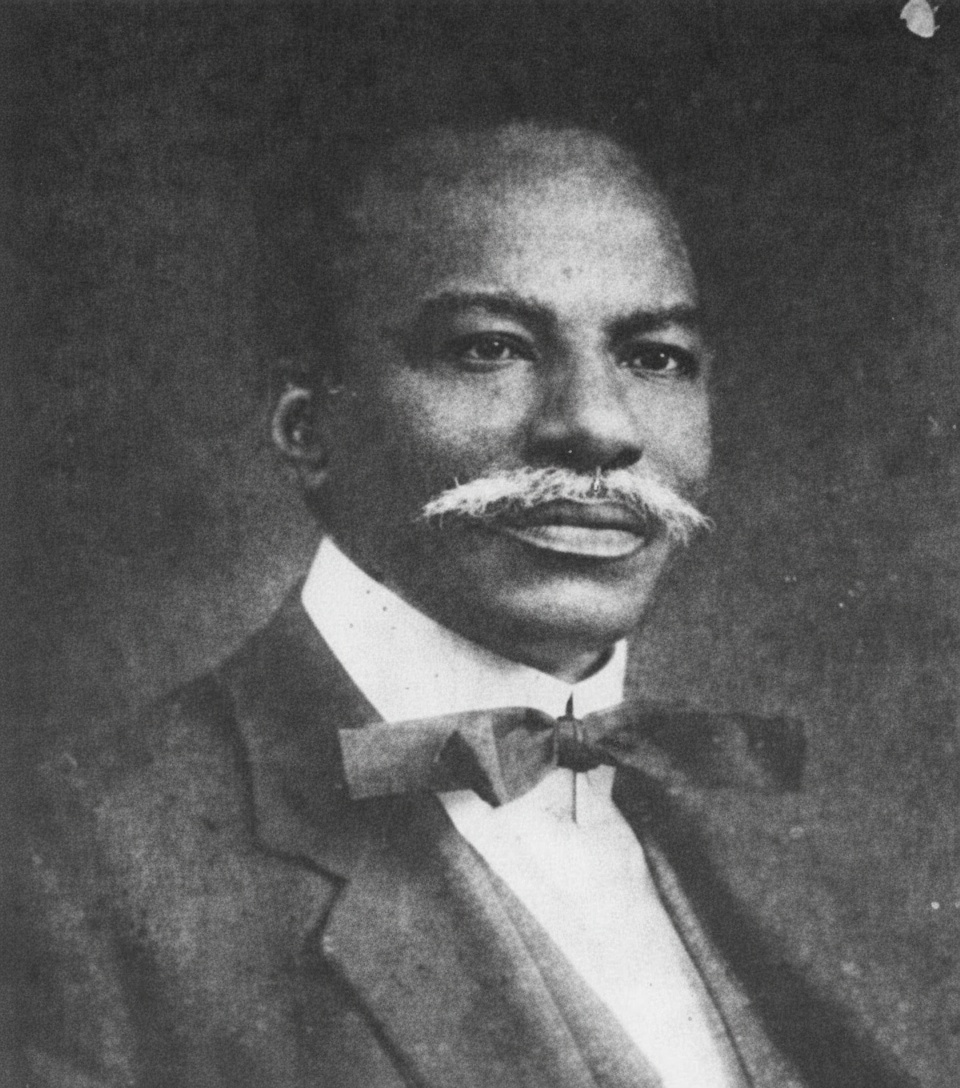

I was born in Lagos on November 14, 1864, into the distinguished Macaulay family, a lineage that connected me to the very fabric of Lagosian aristocracy. My father, Thomas Babington Macaulay, was the founder and first principal of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) Grammar School in Lagos—the first secondary school in Nigeria. He was a man of discipline and learning, a product of the missionary zeal that swept through West Africa.

But it was my mother, Abigail Crowther Macaulay, who connected me to true Yoruba royalty. She was the daughter of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African Anglican bishop, himself a recaptive slave who rose to monumental heights. Through my maternal grandmother, I was descended from King Abiodun of the Oyo Empire, a lineage that instilled in me a deep sense of history and sovereignty long before the British declared their “protection.”

My childhood in the Lagos of the 1860s and 1870s was a unique intersection of Victorian English education and vibrant Yoruba culture. I grew up speaking Yoruba at home but studied Latin and Greek at my father’s school. I witnessed the gradual but unmistakable shift from Lagos as a bustling African port city to Lagos as a British Crown Colony (which it became in 1861, three years before my birth).

Engineering a Future (1877-1893)

The Awakening (1893-1908)

The Water Rate Agitation (1908):

The Lands Controversy:

The Pen as Sword: Journalism & Early Nationalism (1908-1922)

Founding the Nigerian National Democratic Party (1923-1934)

The Later Years: Coalition and Radicalization (1934-1946)

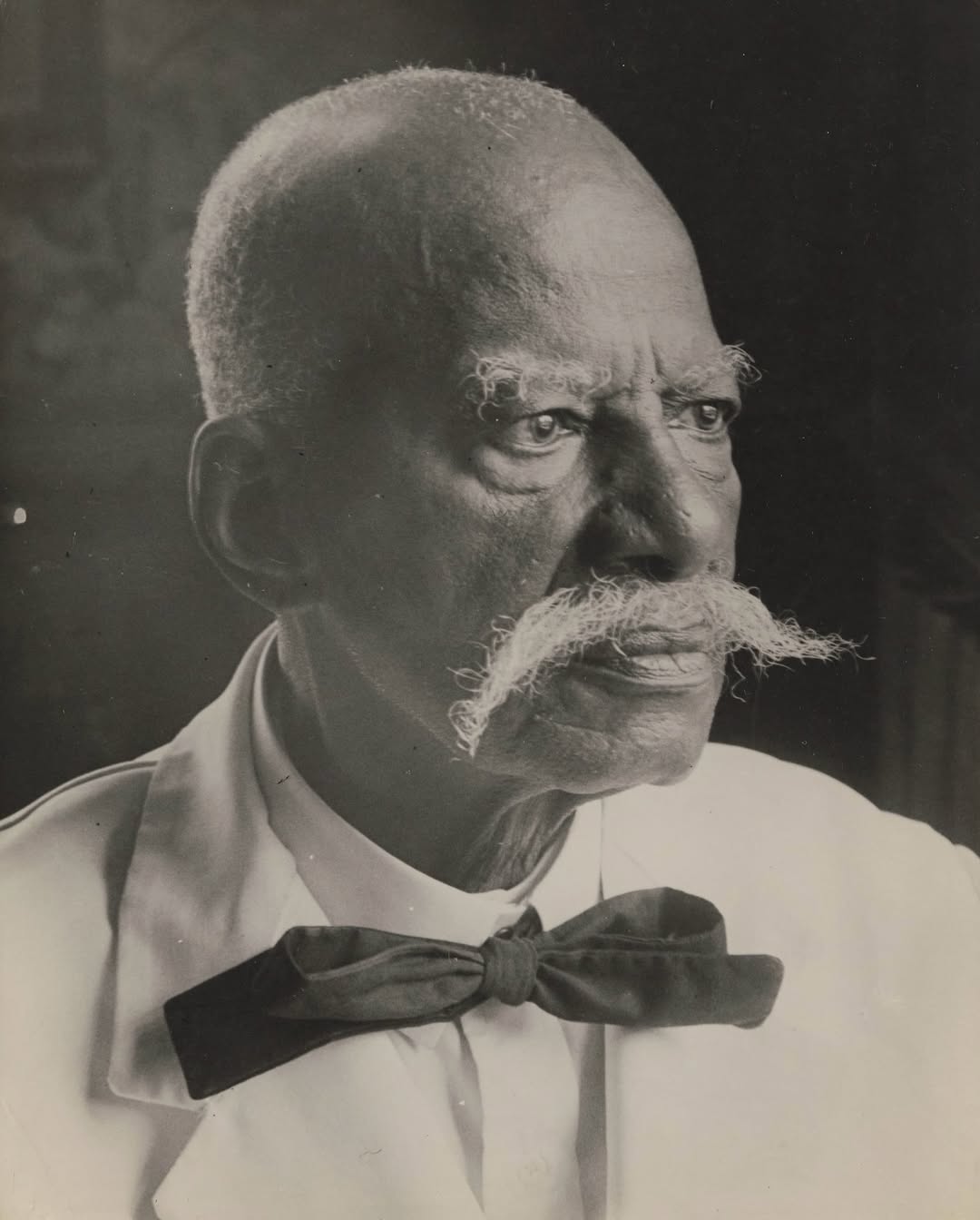

The Final Battle and Legacy (1946)

Epilogue: Reflections

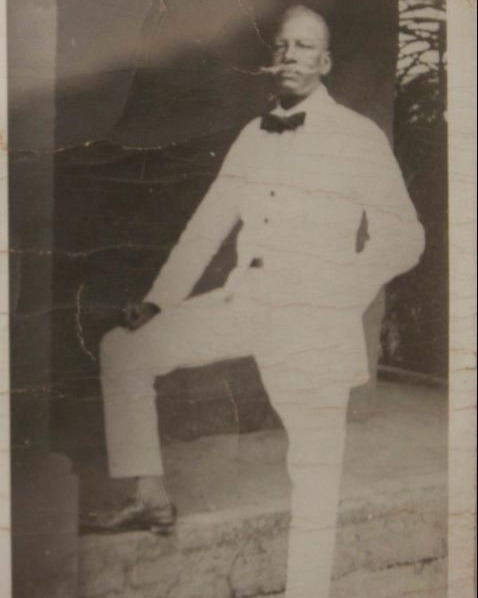

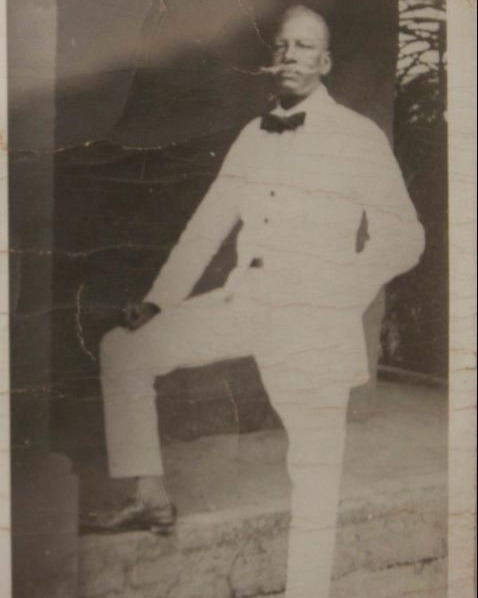

Herbert Macaulay